No Fear No Favour No BULLSHIT...............

The Land Act of 1913 and its alternatives

This year is the centennial commemoration of what many now believe was the one Act that irrevocably put South Africa on the road to Apartheid. Few have been more outspoken about its impact than South Africa’s leader of the opposition, Helen Zille:

The 1913 Land Act was apartheid’s ‘original sin’ because it reserved 87% of South Africa’s land exclusively for white ownership, as the basis of the ‘Bantustan’ policy. It not only dispossessed many black South Africans of the land they owned, but also sought to prohibit black people from ever acquiring land in so-called ‘white’ South Africa.

Unfortunately, history is never that simple. There is no doubt that most white South Africans, English and Afrikaners, at the start of the twentieth century believed that the majority of South Africa’s land – and perhaps even the lands of neighbouring countries – should be proclaimed as ‘white man’s land’. The demand for produce in the rapidly-expanding urban areas combined with low input costs, notably the low cost of black wages, made large-scale agriculture a lucrative enterprise. White farmers were also keen to expand and thus enter the traditional black areas with its highly fertile land. This steady expansion had only one consequence: that, eventually, all black land would have been claimed by white farmers. This didn’t happen though. Instead, a group of white officials in the Department of Native Affairs after unification noted the rapid decline in black land and realised that without statutory intervention blacks may soon own no land at all. The result: the Land Act of 1913. Here’s Hermann Giliomee in The Afrikaners (p. 326):

They saw merit in the idea that a settlement, even if not equitable to blacks, would at least prevent further white encroachment in the reserves. In 1915 the Secretary for Native Affairs referred to a district where fewer than half of the farms formerly owned by ‘natives’ were still in their possession. As the liberal historian W.M. Macmillan pointed out at the time: ‘[Open] competition in land is fatal to the weaker race … Given free right of entry of white into native lands, the natives will presently be landless indeed.

Looking back from our current vintage point, it is easy to assume that the counterfactual to the Land Act of 1913 was a larger share of land for black South Africans; i.e. that instead of the 13%, black South Africans should have received 30%, or 50% or 80%. But what Giliomee suggests here is that that would be a wrong conclusion: instead, in the absence of the Land Act, the land that black South Africans were living on would have been systematically claimed by white settlers, leaving blacks destitute with few alternatives other than to provide their labour to the mines and as farmhands. The Land Act thus protected instead of pilfered land belonging to blacks.

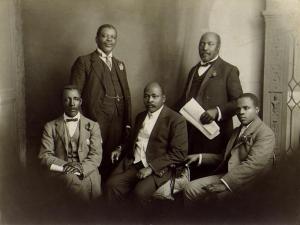

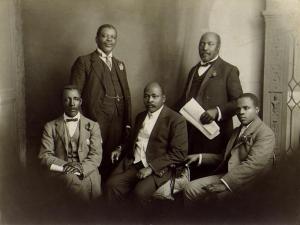

SANNC delegation that went to England to convey African people’s objections to the 1913 Land Act, 1914. L-R: Rev W. Rubusana, T. Mapike, Rev J. Dube, S. Plaatjie and S. Msane. Courtesy of South Africa History Online.

(So here’s a thought experiment: there was no Land Act in 1713 for the Khoi of the southwestern Cape. What if the Dutch East India Company had proclaimed 13% of the Western Cape as Khoi-land. Would Khoi-descendants living in these hypothetical areas today celebrate or abhor the 1713 Land Act? That is an open question. Instead, what happened in the absence of a Land Act was that many Khoi died in the smallpox epidemic of 1713 and those that remained had little choice but to work on settler farms, where many of their descendants still work today.)

The late Lawrence Schlemmer once said that he knows of no former colony – other than South Africa – where the indigenous population continued to live on 30% of the region’s most fertile land after colonisation (I thank Hermann Giliomee for this reference). This is not to suggest that colonisation – or the Land Act – was morally just or defensible, or that it did not contribute to a highly unequal South African society. But before we denigrate the Land Act, we should think about the alternatives. Maybe missionary societies would have acquired some land for black farmers to till. Perhaps white farmers would not have infiltrated black areas to any great extent. But probably not. In all likelihood, black South Africans would have owned considerably less land than what the Land Act of 1913 sanctioned.

Johan Fourie's Blog

Preface Aninka Claassens, Ben Cousins and Cherryl Walker THIS VOLUME encompasses an extraordinary collection of historical and contemporary photographs that singly and collectively speak to the power of land, not only in the turbulent history of this country but also as a significant material and symbolic resource in the day-to-day lives of individuals and communities. The curators and editors have drawn together a compelling set of images of people, land and place that spans more than 100 years in the history of this region, with a focus on the century since the passage of the notorious Natives Land Act in June 1913. The title of this book – Umhlaba (Land) – is direct yet open-ended, allowing for different entry points and multiple forms of engagement with the collection’s overall themes. The history reflected here is, inescapably, one of often brutal conflict and exclusion that has left the present generation with many daunting challenges in the political, economic, social and ecological spheres. However, threaded through this familiar overarching narrative in complex, even challenging ways, are other more affirming accounts of how people have related to or been present on the land. Solidarity, productivity, creativity, spirituality, a sense of place: these experiences of land and landscape that inform the larger history also find expression in the pages that follow. The material presented here comes from many different archives. The wide range of photographers and photographic genres is, in itself, an important achievement of the curators and the team that assisted them. One of the strengths of this collection is the different genres of photography it includes, for example posed studio portraits to commemorate significant milestones in life, alongside photographs taken by activist photographers during the era of forced removals. Not only do the photographs document key events and changes over a century, they do this through different ‘eyes’, some intimate, others seemingly dispassionate. The collection embodies the ever-present tension 10 Umhlaba 1913–2013 between time passing and the immediacy of images captured in the then-present. Many of the images are deeply moving in their powerful evocation of the personal significance of land in the lives of so many South Africans, past and present. The photographic exhibition on which this edited collection is based formed part of the programme of an inter-disciplinary conference, ‘Land Divided: Land and South African Society in 2013 in Comparative Perspective’, held at the University of Cape Town in March 2013 to commemorate the centenary of the passage of the Natives Land Act. This Act, passed by an all-white, all-male Parliament just three years after the Union of South African was established, is widely recognised as foundational for the system of spatial, political and economic marginalisation that was progressively forced on black South Africans after 1910 and which found its apogee under the apartheid regime. The March 2013 conference was a joint initiative of three centres of teaching and research on land and agrarian studies in the Western Cape: the Centre for Law and Society at the University of Cape Town, the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology and the LESA research programme at Stellenbosch University, and the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at the University of the Western Cape. The aim of the conference was to use the occasion of the centenary of the Natives Land Act to provide a platform for critical reflection on not only the uneven manifestations of its legacy across space and time, but also contemporary and future challenges around land and the environment, not all of which can be attributed to this legacy. The conference was, accordingly, organised around four themes: the legacy of the 1913 Natives Land Act; land reform and agrarian policy in southern Africa; the multiple meanings of land (identity, rights, belonging), and ecological challenges. It drew together some 300 delegates – academics, community leaders, policy-makers and officials – in four days of intense debate and discussion. Delegations of rural people attended and spoke at the conference, in addition to academics, public intellectuals, parliamentarians and the Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform. They spoke about their direct experiences of landlessness and their struggles for change. Many of the key challenges facing land reform emerged clearly within their testimonies, for example, Preface Umhlaba 1913–2013 11 the way in which the Traditional Courts Bill of 2012 re-entrenched the ‘Bantustan’ boundaries that are a particularly potent and intractable legacy of the Land Act, the state’s reluctance to transfer restitution land to elected Communal Property Associations, and the absence of effective postsettlement support. The photographic exhibition on which this book is based, which opened at the Iziko National Gallery in Cape Town on 25 March 2013, was a high point of the proceedings. It gave powerful visual expression to the conference themes while challenging viewers, then and in the months to follow in Cape Town and later in Johannesburg, with previously unseen archival material and the unexpected framing of issues and juxtapositioning of images. The exhibition managed, in a way that is more difficult for academic conferences, to convey its meanings directly and personally to a wide range of differently situated people. Photography can, perhaps, be a more direct and democratic medium than words, especially those deployed at academic conferences, with all their complications of language and separate disciplines and bodies of knowledge. We were proud, as members of the Conference Steering Committee, to have collaborated with the curators of the exhibition in this way. The centenary year of the Natives Land Act presented us with a major opportunity to reflect on the significance of land, historically and in contemporary society. The legacy of this Act is still etched in South Africa’s deeply divided countryside and racialised inequalities. Yet what is also becoming increasingly apparent at the start of the third decade of political democracy in this country is that the complex intersection of social, economic and environmental issues which shape relationships to land cry out for fresh analysis and revitalised understandings. This book makes a significant contribution to this task of reflection and review. Dr Aninka Claassens is chief researcher and director of the Rural Women’s Action Research Programme of the Centre for Law and Society at the University of Cape Town; Ben Cousins is Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation Chair in Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies and senior professor at the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) of the University of the Western Cape; Cherryl Walker is professor of sociolocy and social anthropology at Stellenbosch University. Aninka Claassens, Ben Cousins and Cherryl Walker 12 Umhlaba 1913–2013 PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN: Sol Plaatje, far right, with other members of the South African Natives National Congress (SANNC) delegation which travelled to London in 1914 to convey their objections to the 1913 Natives Land Act to the British government. Others are, from left to right, Thomas Mapike, Reverend Walter Rubusana, Reverend John Dube and Saul Msane. Plaatjie remained in England to fight for their cause until 1917. Courtesy of Silas T Molema and Solomon T Plaatje Collection, Historical Papers Research Archive, The Library, University of the Witwatersrand.

Wits Umhlaba

COMMENTS BY SONNY

WE ARE NOT SHEEP AND DO NOT BELIEVE WHAT JACOB ZUMA SAYS................

ZUMA HAS COMMITTED HIGH TREASON AGAINST HIS OATH OF OFFICE!

Preface Aninka Claassens, Ben Cousins and Cherryl Walker THIS VOLUME encompasses an extraordinary collection of historical and contemporary photographs that singly and collectively speak to the power of land, not only in the turbulent history of this country but also as a significant material and symbolic resource in the day-to-day lives of individuals and communities. The curators and editors have drawn together a compelling set of images of people, land and place that spans more than 100 years in the history of this region, with a focus on the century since the passage of the notorious Natives Land Act in June 1913. The title of this book – Umhlaba (Land) – is direct yet open-ended, allowing for different entry points and multiple forms of engagement with the collection’s overall themes. The history reflected here is, inescapably, one of often brutal conflict and exclusion that has left the present generation with many daunting challenges in the political, economic, social and ecological spheres. However, threaded through this familiar overarching narrative in complex, even challenging ways, are other more affirming accounts of how people have related to or been present on the land. Solidarity, productivity, creativity, spirituality, a sense of place: these experiences of land and landscape that inform the larger history also find expression in the pages that follow. The material presented here comes from many different archives. The wide range of photographers and photographic genres is, in itself, an important achievement of the curators and the team that assisted them. One of the strengths of this collection is the different genres of photography it includes, for example posed studio portraits to commemorate significant milestones in life, alongside photographs taken by activist photographers during the era of forced removals. Not only do the photographs document key events and changes over a century, they do this through different ‘eyes’, some intimate, others seemingly dispassionate. The collection embodies the ever-present tension 10 Umhlaba 1913–2013 between time passing and the immediacy of images captured in the then-present. Many of the images are deeply moving in their powerful evocation of the personal significance of land in the lives of so many South Africans, past and present. The photographic exhibition on which this edited collection is based formed part of the programme of an inter-disciplinary conference, ‘Land Divided: Land and South African Society in 2013 in Comparative Perspective’, held at the University of Cape Town in March 2013 to commemorate the centenary of the passage of the Natives Land Act. This Act, passed by an all-white, all-male Parliament just three years after the Union of South African was established, is widely recognised as foundational for the system of spatial, political and economic marginalisation that was progressively forced on black South Africans after 1910 and which found its apogee under the apartheid regime. The March 2013 conference was a joint initiative of three centres of teaching and research on land and agrarian studies in the Western Cape: the Centre for Law and Society at the University of Cape Town, the Department of Sociology and Social Anthropology and the LESA research programme at Stellenbosch University, and the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) at the University of the Western Cape. The aim of the conference was to use the occasion of the centenary of the Natives Land Act to provide a platform for critical reflection on not only the uneven manifestations of its legacy across space and time, but also contemporary and future challenges around land and the environment, not all of which can be attributed to this legacy. The conference was, accordingly, organised around four themes: the legacy of the 1913 Natives Land Act; land reform and agrarian policy in southern Africa; the multiple meanings of land (identity, rights, belonging), and ecological challenges. It drew together some 300 delegates – academics, community leaders, policy-makers and officials – in four days of intense debate and discussion. Delegations of rural people attended and spoke at the conference, in addition to academics, public intellectuals, parliamentarians and the Minister of Rural Development and Land Reform. They spoke about their direct experiences of landlessness and their struggles for change. Many of the key challenges facing land reform emerged clearly within their testimonies, for example, Preface Umhlaba 1913–2013 11 the way in which the Traditional Courts Bill of 2012 re-entrenched the ‘Bantustan’ boundaries that are a particularly potent and intractable legacy of the Land Act, the state’s reluctance to transfer restitution land to elected Communal Property Associations, and the absence of effective postsettlement support. The photographic exhibition on which this book is based, which opened at the Iziko National Gallery in Cape Town on 25 March 2013, was a high point of the proceedings. It gave powerful visual expression to the conference themes while challenging viewers, then and in the months to follow in Cape Town and later in Johannesburg, with previously unseen archival material and the unexpected framing of issues and juxtapositioning of images. The exhibition managed, in a way that is more difficult for academic conferences, to convey its meanings directly and personally to a wide range of differently situated people. Photography can, perhaps, be a more direct and democratic medium than words, especially those deployed at academic conferences, with all their complications of language and separate disciplines and bodies of knowledge. We were proud, as members of the Conference Steering Committee, to have collaborated with the curators of the exhibition in this way. The centenary year of the Natives Land Act presented us with a major opportunity to reflect on the significance of land, historically and in contemporary society. The legacy of this Act is still etched in South Africa’s deeply divided countryside and racialised inequalities. Yet what is also becoming increasingly apparent at the start of the third decade of political democracy in this country is that the complex intersection of social, economic and environmental issues which shape relationships to land cry out for fresh analysis and revitalised understandings. This book makes a significant contribution to this task of reflection and review. Dr Aninka Claassens is chief researcher and director of the Rural Women’s Action Research Programme of the Centre for Law and Society at the University of Cape Town; Ben Cousins is Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation Chair in Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies and senior professor at the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS) of the University of the Western Cape; Cherryl Walker is professor of sociolocy and social anthropology at Stellenbosch University. Aninka Claassens, Ben Cousins and Cherryl Walker 12 Umhlaba 1913–2013 PHOTOGRAPHER UNKNOWN: Sol Plaatje, far right, with other members of the South African Natives National Congress (SANNC) delegation which travelled to London in 1914 to convey their objections to the 1913 Natives Land Act to the British government. Others are, from left to right, Thomas Mapike, Reverend Walter Rubusana, Reverend John Dube and Saul Msane. Plaatjie remained in England to fight for their cause until 1917. Courtesy of Silas T Molema and Solomon T Plaatje Collection, Historical Papers Research Archive, The Library, University of the Witwatersrand.

Wits Umhlaba

COMMENTS BY SONNY

WE ARE NOT SHEEP AND DO NOT BELIEVE WHAT JACOB ZUMA SAYS................

ZUMA HAS COMMITTED HIGH TREASON AGAINST HIS OATH OF OFFICE!

Thanks for sharing, nice post! Post really provice useful information!

ReplyDeleteAn Thái Sơn với website anthaison.vn chuyên sản phẩm máy đưa võng hay máy đưa võng tự động tốt cho bé là địa chỉ bán may dua vong tu dong tại TP.HCM và giúp bạn tìm máy đưa võng loại nào tốt hiện nay.